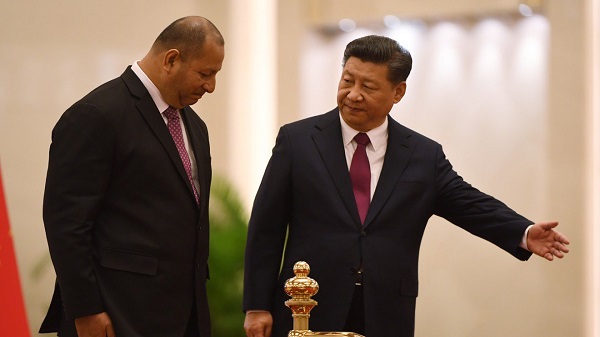

China: the real reason Australia’s pumping cash into the Pacific? Featured

Papua New Guinea’s Prime Minister Peter O'Neill, Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and Prime Minister of the Solomon Islands Rick Houenipwela. Photo: AFP

Papua New Guinea’s Prime Minister Peter O'Neill, Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and Prime Minister of the Solomon Islands Rick Houenipwela. Photo: AFP

1 August, 2018. When the leaders of Australia, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands this month signed off on a deal to link the three countries via an undersea internet cable, Canberra positioned itself as a thoughtful neighbour, eager to help developing nations in its own backyard.

“We spend billions of dollars a year on foreign aid and this is a very practical way of investing in the future economic growth of our neighbours in the Pacific,” said Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, whose country is spending A$137 million dollars – two-thirds of the project’s cost – to give the two countries access to reliable high-speed internet services for the first time.

But what Turnbull did not mention at the signing ceremony in Brisbane on July 11, when he was flanked by Solomon Islands Prime Minister Rick Houenipwela and Papua New Guinea Prime Minister Peter O’Neill, was that Australia has another, arguably deeper motivation for taking on the project: countering China’s growing influence in the region.

“The Pacific is of critical strategic importance for Australia,” Jonathan Pryke, the director of the Lowy Institute’s Pacific Islands Programme, told This Week in Asia. “Geographically, we are wedded to the region.”

In recent years, China has showered small Pacific nations such as Vanuatu, Tonga and the Solomon Islands with aid and concessional loans for infrastructure such as roads, ports and government buildings. The Sydney-based Lowy Institute estimates Beijing transferred more than US$1.7 billion to the region via its opaque foreign aid programme between 2006 and 2016.

Australian officials, usually obliged to adopt a diplomatic touch with China, the country’s biggest trade partner, have increasingly made their displeasure with the shifting status quo clear.

Last month, Foreign Minister Julie Bishop expressed concern that China was imposing debt burdens on small nations that could eventually threaten their sovereignty.

“We want to ensure that they retain their sovereignty, that they have sustainable economies and that they are not trapped into unsustainable debt outcomes,” Bishop told The Sydney Morning Herald. “The trap can then be a debt-for-equity swap and they have lost their sovereignty.”

During a visit to Micronesia and the Marshall Islands only a fortnight earlier, Bishop had said Australia wanted to be the preferred partner of Pacific island nations, declaring the region Australia’s “part of the world”.

China has fought back against such suggestions. Its foreign ministry has lambasted the “wrong remarks of the Australian side”, challenging Canberra to give examples of Beijing burdening countries with unsustainable debt.

Already by far the biggest donor to the region, Canberra has ramped up its own engagement in the Pacific, boosting assistance even while slashing its overfall foreign aid budget. Canberra allocated A$1.3 billion this year in aid to Pacific nations, a rise of almost 20 per cent.

Anthony Bergin, a senior analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, told This Week in Asia Australia felt the need to “step up” as China was wielding more influence on its doorstep.

“It’s the only area that Australia didn’t cut its aid,” Bergin said of Australia boosting funding for development projects in the region. “Everyone talks about cuts to aid but the Pacific was cauterised.”

Beyond shifting dynamics in the region generally, Australia’s concerns have been amplified by specific developments related to national security sensitivities.

When the Solomon Islands originally tapped Chinese tech giant Huawei to construct its undersea cable in 2016, Australia stepped in with a more lucrative offer to deprive the firm of access to the country’s telecommunications infrastructure. Since 2012, Canberra has banned Huawei from any involvement in its broadband network due to the firm’s alleged ties to the Chinese Communist Party.

In April, Fairfax Media reported that China was in discussions with Vanuatu to establish a military base on the island, which is less than 4,000km from the Australian mainland. Having already tested relations with Beijing by announcing new anti-foreign interference laws widely seen as a response to alleged Chinese meddling, Turnbull said the report was of “great concern”. The Chinese and Vanuatuan governments both rejected the report as baseless.

“There are genuine concerns there, and that’s part of a very long tradition in Australia’s approach to the Pacific, which goes back perhaps 150 years,” said James Batley, a former foreign service official who served as Australia’s High Commissioner to Solomon Islands.

“Certainly Australia would say that it has legitimate security interests in this part of the world.”

Although Australia and China look likely to butt heads in the Pacific, analysts say engagement in the region needn’t be a zero-sum game.

“The Pacific is large enough for all of us to be operating in and there is severe development need in the Pacific that we can all help to address,” said Pryke.

“The reality is China is in the Pacific to stay, so is Australia,” he added. “So we all have to figure out how to work together for the best interests of the Pacific region.”

Bergin said it would be “patronising” to believe that Pacific nations didn’t know what they were doing or were incapable of reaping the benefits of close relations with both countries.

“It’s not as if anyone in the region is thinking, ‘Well we are not going to be Australia’s friend any more, now we’re just going to be China’s friend,’” he said.

“That’s just silly. That’s not how international relations works.”.

-South China Morning Post